How Kids Learn to Navigate the City (and the World), in Five Designs

Critic Alexandra Lange talks about the objects and places that represent a-ha moments in child-centered design.

In the era of Marie Kondo, the streamlining of our material lives still runs into one big obstacle: parenthood. “To have a child is to be thrown suddenly, and I found rather miraculously, back into the world of stuff,” writes design critic Alexandra Lange in her new book, The Design of Childhood. As Lange and countless other parents discover, you might use a baby-monitor app and have episodes of Peppa Pig on the iPad, but living with children means swimming in a sea of tactile objects—teething necklaces and strollers, play kitchens and board books.

Lange became fascinated by these objects, and by the series of spaces that delimit kids’ worlds as they grow. “I came to see each successive stage of child development as an opportunity for encounters with larger and more complex environments,” she writes. Her book tells the history of designing for children, describing their engagement with the material world in Matryoshka-doll fashion—from toys, to their homes, to schools and playgrounds, and finally to the city around them.

CityLab talked with Lange about five objects and places from the book that represent a-ha moments in child-centered design.

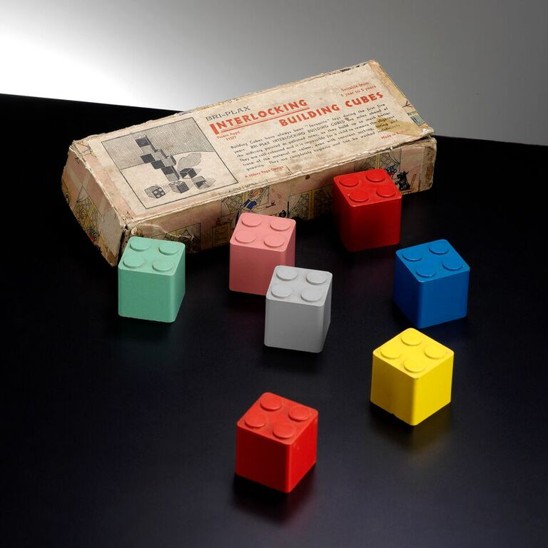

Let’s start with toymaker Hilary Page and his self-locking building bricks. These were plastic blocks with raised bumps and an open bottom. Which sounds an awful lot like another toy that we’re more familiar with …

Hilary Page is one of those people that I discovered in researching the book that I was just like, “Why don’t we know about them?” All the ideas we have about childhood now—about it being crafty and about maker culture—he naturally had.

He grew up in England and his father worked in the lumber industry, and one year for his birthday, his father bought a giant pile of scrap lumber and put it in the backyard. Page grew up making his own toys, making his own games, playing in the wood pile. Having a wood pile or sand pile is definitely a theme running through the book.

[Page’s toy company] Kiddicraft sold a lot of wooden toys, which was standard at that time. In the meantime, Page himself was visiting nursery schools each week, sitting there, watching what [the children] wanted to do. Even though he wasn’t trained in child observation as a psychologist or educator, he was doing it himself.

Around this time, he became really interested in plastic. He created another company called Bri-Plax to make plastic toys. The first ones were stackers [and] rubber duckies. Then he thought, “I can make a plastic block to improve on the [wooden] building block.”

He came up with the idea of the interlocking cube. The four studs on top would interlock with the open bottom, so it made a bond. In 1940, he gets a British patent for the “interlocking building cube.” The market’s there, but he’s pretty small-time, and he can’t make any of them during the war, because all the plastic had to go to the war effort.

In 1945 he starts marketing them again under the Kiddicraft brand, and at that point he also makes and patents what he’s calling a “self-locking building brick” that is basically two studs by four studs—which is the format of the classic basic Lego piece.

So how do we get from Hilary Page to Lego? There’s actually a really simple connection. Page used a specific type of plastic molding machine to make his brick. The manufacturer of that machine tried to sell it to other people, among them, the Christiansen family [in Denmark], who owned Lego. [Some of] the sample pieces that the manufacturer included [were] Page’s Kiddicraft bricks. There’s this direct manufacturer connection between the Christiansens and Page. [This was] later talked about in some court cases around the matter of patent designs.

Because of their great marketing prowess, which building system took over the world? It wasn’t Kiddicraft, it was Lego. They started making their own bricks in 1949 and have a Danish patent [from 1958] with design modifications [to Page’s bricks].

Did they do something different to the corners?

The Kiddicraft blocks have rounded corners. They look a little softer, and were probably easier to mold on the molding machine. The Christiansens realized it’s better for a building system for everything to be squared up. They square up the corners and make them metric. At a later point, they add the tubes on the bottom. Open bottoms wouldn’t fit as tightly as present-day Legos.

That, I would argue, really makes it into a different product. It’s a major design refinement.

In the early days, they are marketing the blocks as a pretty free-form toy. They suggest you should build houses with it, because that’s what blocks have traditionally been used for, but it’s pretty much up to the child. But Lego isn’t successful until they make it more systematized and create the idea of annual sets.

They issue a basic house set, and new sets that add elements of the town. You get a house, then you get a gas station. Then you get a school, and a factory. Suddenly, families could see this wasn’t a one-off—this was something you could add onto year after year. Build your own town on the floor of your playroom.

That’s part of what makes Lego successful. They systematize it and make it into a toy where there’s an expectation of longevity. They make it more addictive, essentially. The idea that we only made [Lego] commercial in the ‘80s is actually kind of incorrect.

Are interlocking plastic bricks Good Toys, or Bad Toys? You write about this long-standing cultural distinction.

I would say they can be either, or they are both. The good toys/bad toys distinction is really interesting. A “good” toy is something that is natural, long-playing, hard-wearing, open-ended. It probably has minimal or no decoration. A “bad” toy is something that is highly specific, probably painted or made of a very cheap material, and has only one purpose. In the early years, this would have been the distinction between wooden building blocks and something like a tin windup toy, which, after a week, would probably break.

There’s still a lot of educators who really believe in wooden toys. Not all wooden toys are good—they still have to be well-crafted, we still have to know the origins of the materials. Page wasn’t wrong that if you have a small child who likes to chew on things, a wooden block is not necessarily the best thing to give them.

I feel like in the 21st century, we have to let plastic in, although we have to know the origins of it. Lego is looking into making some of its pieces out of plant-based plastic.

Another Scandinavian design has an important role in your book, the Tripp Trapp Chair. What did that chair get right that previous high chairs and kids’ chairs got wrong?

The story of the Tripp Trapp Chair is again the story of close observation of children. In this case, it was Peter Opsvik observing his own son, Thor, trying as a toddler to get up to the table. With most high chairs, a kid can’t get into it on their own. It has a big tray in front of a footrest, so the parent has to get the child in and out. If you’ve had a small child, you remember how tiring it is: in and out, and they’re often covered in food.

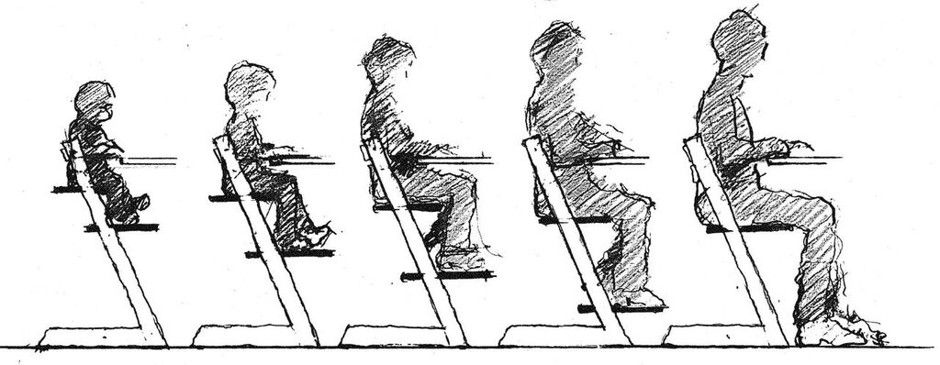

Opsvik wanted to give his son a way to get up to the table at the same height as the parents. He wanted to give him the responsibility and a sense of being at the table. The [chair’s] footboard is very wide, so the kid can use it to get up, but a v-shaped base makes it really stable so it’s impossible to tip over. The idea of the chair is that the child can get up and down, and then you can also adjust the foot rest and seat for multiple heights.

I bought one of these for my son when he was one, and I thought he would pass it down, but he kept it, and now we have two of them, and my kids who are seven and 10 still use them as chairs and as step ladders to get snacks.

The chair embodies two themes. One is the idea of freedom and responsibility: Your child should be able to decide to get up and down from the table themselves. That’s part of inviting them into the family, rather than restricting their movement. Then there’s the idea of variation, of furniture as well as toys that can grow with your child, that aren’t throwaway items.

A real market for children’s furniture only started to grow in the ‘20s and ‘30s. The idea of spending money on children is a fairly modern idea. Children worked through the 19th century and even into the early 20th century, and the spaces they had in houses were often sort of cast-off spaces: “Oh, you can play in the attic.” [Children’s] furniture would be an adult table with the legs shorter.

The idea of making child-specific, child-sized things started with aristocratic homes, and not so long ago [became] a mainstream thing. Following that, especially in the postwar era, we get developers and architects starting to design houses with child-specific spaces, and that becomes part of the conversation.

In a way, you can read the shift in attitudes toward children and parenting in the evolution of the high chair—from something that controls fidgety bodies to something that accommodates them.

The design of Crow Island School [built in 1940] outside of Chicago received wide publicity at the time and was included in an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. What made it so revolutionary?

I think it was one of the first schools to incorporate modern design ideas. Obviously through the ‘20s, ‘30s, and ‘40s, European Modernism had begun to infiltrate American architecture. But there wasn’t so much building happening in 1940. After the war, when people saw the baby boom coming, there was all this school construction, so [Crow Island] was ideally placed to be a model. It was also designed by famous architects and run by a famous educator. It had all these elements that made it easy to publish and treat as a model.

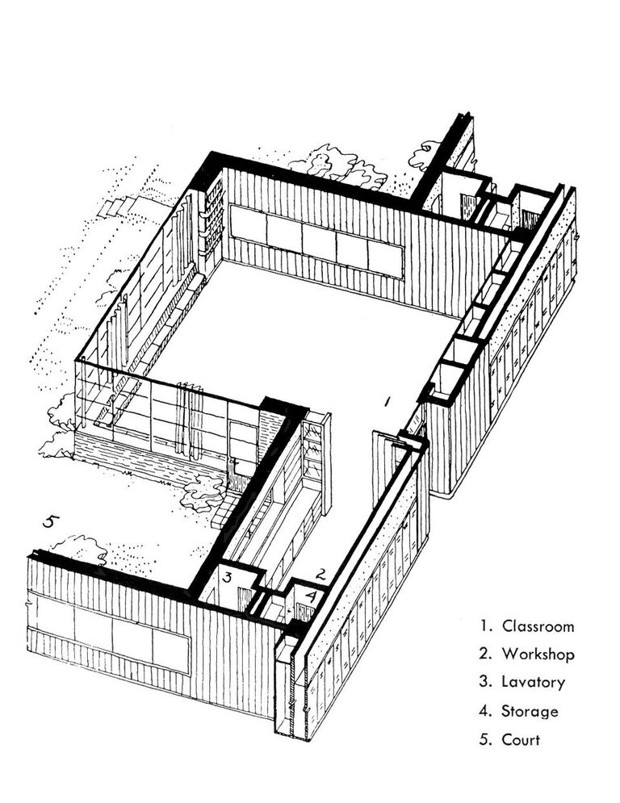

The prewar [American] school was this big, chunky, multistory place with a schoolyard in back and classrooms lined up in a row. Crow Island is all one-story; it has these fingers going out into the landscape, and each classroom has an outdoor space. The classrooms are L-shaped. And in part of the L, they have a sink and counter [for art and science projects] and a small bathroom. They have big windows with a window seat on the outer edge, and kids were allowed to read to themselves on the window seats.

Instead of rows of desks, there were little chairs and tables that were designed by Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames, and made by the Works Progress Administration, the FDR program for artisans during the war. The light switches are all at child height. The door knobs, too. The auditorium benches get smaller from back to front. Those benches are also really beautiful. They’re bent wood, and look like Eames and Saarinen furniture.

The school is a beautiful design, and it also had this child-first ethos embedded in it. The classroom wasn’t rigid during the day. Kids could do different things in different areas: The teacher became a kind of choreographer. “Now we’re going to paint; now we’re going to sit at the table and do a workbook.” All the ideas [at the time] about a more open and progressive education, and one that happens in nature, are embedded in it.

Are there common features in schools today that we can trace back to Crow Island?

The first thing to go in a lot of the imitation schools was the sink area in the classroom. The imitation schools square [the L] off and eliminate the wet zone and often the bathroom. In terms of the space, I feel like without the L shape, then it’s just a box, which has more or fewer windows. The material qualities get degraded.

I think that a lot of the [pedagogical] ideas are still with us and haven’t been discredited. The idea of children doing head-down work, and then taking a break and building with blocks in the corner is definitely still there.

I was amazed to learn that the architect Aldo Van Eyck designed more than 700 playgrounds in Amsterdam. What does a Van Eyck playground look like?

Especially for architects, who are often fighting tooth and nail to get one project built, the idea that you could be the author of 700 of anything is amazing.

Aldo Van Eyck is an architect I heard about in architectural history classes, but his interest in children was never emphasized. [In my research] I found plenty of famous architects who designed for children and were quite interested in children, but the way that architectural history is taught does not privilege that work. It paints that work as lesser to a monument or museum for adults. I think it’s important as a corrective to say that architects took this work for children extremely seriously.

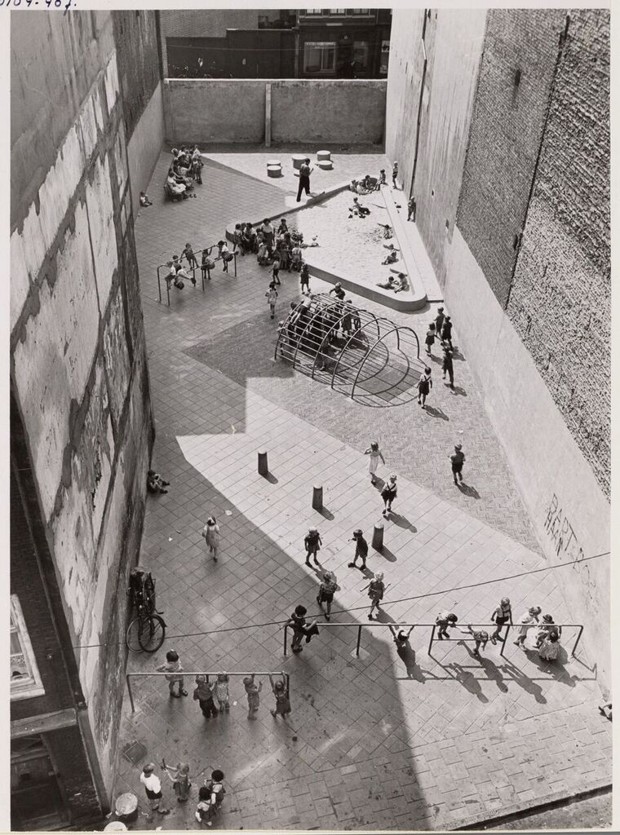

Van Eyck was a member of a variety of avant-garde architecture groups. But he spent most of his career working for the Amsterdam public works department under a woman named Jacoba Mulder. He designed 700 playgrounds for the city, beginning in 1947. These really came about primarily because neighborhoods asked for them. They had a park that people weren’t using, or a vacant lot, possibly because of war [damage]. They wrote to the public works department.

Van Eyck would go out there and look at the site, and for each site he created a custom composition of these play elements he developed. It was a kit-of-parts system, but no two playgrounds were alike. He would look at each site and then deploy his basic elements. These were made of sturdy materials—I would call them infrastructural materials.

There was always a sandbox, round or square, and it had a thick edge people could sit on. There were iron climbing hoops in a row, and later van Eyck designed an “igloo,” which could be a fort or a kind of interior space, but kids could also climb on top of it. Then [the playgrounds] also had these concrete toadstools. There are photos of kids jumping from one to another, or sitting on one and having a snack. Each piece has dual purposes and is also uber-sturdy.

Are they in use, still popular?

They exist, but two women put together a booklet called Aldo van Eyck: Seventeen Playgrounds, documenting the 17 that exist in close to their original state. They felt at that time that people weren’t valuing them. Some of the equipment has now been acquired by the Rijksmuseum. I don’t know if the 17 are going to hang on or not.

These were very much supposed to be pocket playgrounds, and not destination playgrounds. The idea really was to leave as much as possible to the child’s imagination. [Van Eyck] represents this abstractionist line of playground design that [Isamu] Noguchi also goes into, which says the designer can make the equipment, but the children bring the story.

I do think these playgrounds might become boring for older children. There comes a time when children need bigger equipment or more equipment, and if they don’t get it, they just climb on top of everything. I think that’s a problem a lot of cities have. What kind of provision can there be for [playgrounds] in the city?

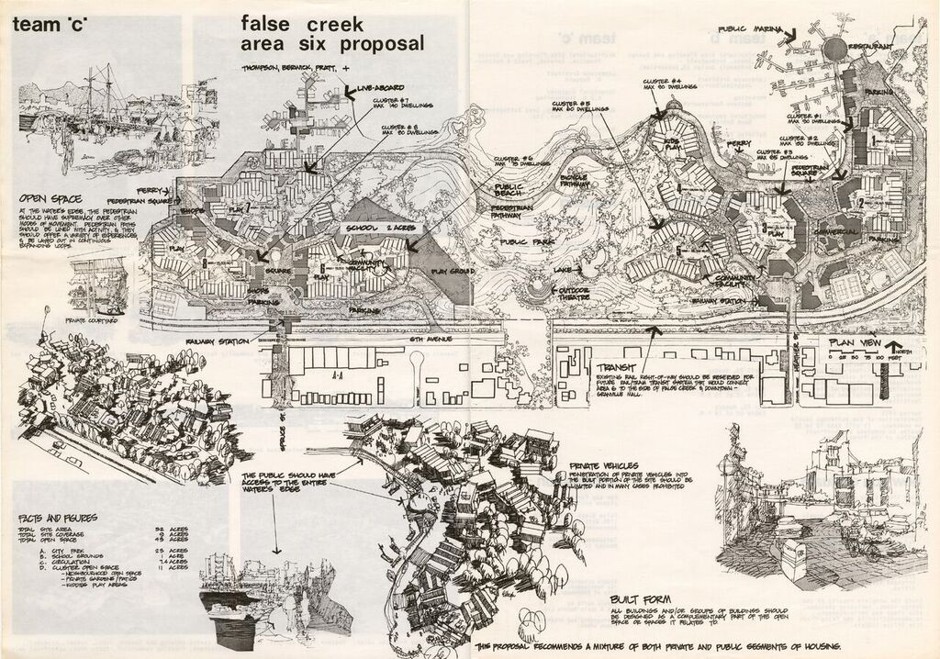

You write that the False Creek South neighborhood in Vancouver is one you could see yourself living in. Why?

The bigger inference from this question is about how we talk about families in the U.S., and that every family is considered an island that must provision for itself. The idea of designing a neighborhood for families as part of a public good just goes against the whole way we think about family life.

Family life has become so stressed in this country. That’s connected to the way we design cities, and to things like commute times, not having communal play spaces, and having streets be unsafe. All of those things take more of the parents’ time or money to navigate, because the child can’t do it on their own. [If you said,] “We want to build a family-friendly city,” it would seem almost un-American.

More people with children want to stay in cities; more people who live in suburbs want walkable amenities. Both of those desires should point to some of the kinds of urban design I talk about.

The first principle [that makes False Creek South successful] is layers of space, from private to public—layered space that is largely car-free. The one place I saw that was in this neighborhood built in the 1970s.

It’s all in a very 1970s mode. It’s mostly brown, and there are a lot of stair-stepping roofs and balconies. Each set of housing wraps around a courtyard. Most courtyards have some kind of play equipment, some open lawn, and then a flower garden or vegetable garden that’s communal.

Each apartment has a private deck or enclosed patio overlooking a shared courtyard, and off of the courtyard is a party room. It’s a classic example of, “Our private space is a little bit smaller, but we have this communal space so we can have a party for 30 people. We don’t need to have a giant living room for the one time a year we do that.” Most of the parking is submerged in the back. When you exit one of the courtyard groups there is a street with a low speed limit and a public path running along the waterfront—essentially a woonerf—and a big public park.

There’s a school within the community, a bodega. Those are also things that are important for children’s independence, to be able to walk to school and get a popsicle on their own. They can also access this park that has play structures and woodland. For older kids and teenagers, I think that’s important.

Courtyard housing and row housing are probably the places to get more families to move for greater density, rather than high-rises. That’s the point of ground-oriented housing: If you need to talk to your child, you can yell out to them. You don’t need to see them all the time. There are other people out there; there’s someone gardening.

What are the main fixes and policies you’d suggest to make cities more child-friendly?

Number one has got to be street safety. It doesn’t matter how many amenities you have for families or how nice playgrounds are if kids can’t get to them safely on their own. That limits how much time they can spend [there] and how much independence they have in exploring their neighborhood. This is a huge topic right now, especially in New York. NACTO is working on family-friendly street guidelines right now. I hope that will broaden the discussion.

Also, playgrounds for multiple ages and abilities, either on one site, or sprinkled throughout the neighborhood. I was just talking with someone from the parks department and asked, “Does anyone ever do a playground audit of a neighborhood, so they could be diversified?” So that there could be different spots where it was clear to children they were welcome. Could [cities do playground maintenance] smarter, could they coordinate with the department of transportation? If you silo education and transportation and housing and parks, it’s very difficult to achieve a family-friendly neighborhood.

The housing component is thinking about new housing as being built not just for transient singles and couples, but including more larger apartments, and thinking about ground orientation. A percentage of two- and three-bedroom apartments is part of Vancouver’s guidelines. Toronto also has new guidelines for family-friendly planning that they put out.

The other thing would be schools and childcare. When you’re building more family-sized apartments, you should also be building an up-to-code space for childcare on the ground floor of the building. Don’t invite families in and make them have to drive their kids back to the suburbs for childcare.