Now Is the Time to Overreact

If the measures we're taking to fight the coronavirus work, they'll look excessive later on. But the alternative is worse.

Updated at 8:26 p.m. ET on March 16, 2020.

Already, the kids were starting to get a little stir-crazy. Yesterday was the second day my family and I had been cooped up at home. None of us is infected with the coronavirus, as far as we know, nor at greatest risk. But with public-health officials urging all Americans to reduce social contact, we’re doing our small part to help lower transmission rates and avoid overcrowding hospitals, for the foreseeable future. So we chose a responsible compromise to cure cabin fever: piling into the minivan to pick up (Lysol-wiped) boxes of Girl Scout cookies from a family friend.

Given all the alarm, I half-expected empty streets and storefronts but instead saw something more unnerving: It looked like any other Sunday afternoon in Atlanta. The roads weren’t packed, nor were they empty. A queue of hungry bodies snaked out the door of the Hattie B’s Hot Chicken, like every weekend. Hipsters congregated along the popular BeltLine trail, ambling as usual.

From my perspective, staring down the barrel of a “once-in-a-generation pathogen,” as the former U.S. Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb put it, everyone else was underreacting. It’s fine to go outside, to walk or jog, to garden or mow the lawn. But the people cramming together en masse were doing the exact thing we’re being told to avoid right now. Even so, faced with the ordinary routines all around us, I couldn’t help wondering: Am I overreacting?

The last time I’d left the house was Friday evening, to pick up my son from the airport. He was returning from college out of state for spring break—maybe one that lasts until summer. As we wound up the dark freeway, he remarked at how normal everything seemed. The scene was not reminiscent of a zombie apocalypse, like in The Walking Dead, he told me, where you can see the danger and try to avoid it. For cities like Atlanta, in a state with more than 120 reported cases and counting, there’s enormous cognitive dissonance in avoiding an invisible microbe that’s spread, in part, by human hosts who exhibit no visible symptoms. The invisibility justifies, for some, adopting extreme caution or, for others, shunning that same caution—with no immediately apparent consequence either way.

[Read: The dos and don’ts of ‘social distancing’]

That lag explains the fear of overreaction: At best, hunkering down is inconvenient; at worst, for some, it’s impossible. Doing something different from the norm feels shameful—as does risking having gone too far in hindsight. But ultimately, the protective measures Americans are newly undertaking will always seem like overreactions, so long as they work. This is the paradox of the present moment: If we wait until the problem is sufficiently visible to transform overreaction into mere reaction again, we will have been too late.

In early 2014, a blizzard crippled Atlanta, where snow is rare, snow-clearing equipment is scant, and citizens don’t know how to drive in bad weather. The storm dropped an embarrassingly small measure of snow, perhaps a couple inches, and some people ended up stuck in freeway traffic for more than 18 hours. That time, the roads did look apocalyptic, just like a scene from The Walking Dead, in fact.

The storm only became a calamity because local officials didn’t plan for it in advance, and then responded poorly once the circumstances proved dire. The first mistake was failing to close schools and workplaces beforehand, when the storm was inbound. The second was releasing everyone at once into the weather when that first plan failed. In the years since, municipal officials and business leaders have learned their lesson: They delay or cancel work and school at even the slightest sign of possible winter storms. Knowing what could go wrong because it already did makes it easier to justify taking action that would otherwise seem like overreaction. The storm is like the zombies, now, made material in recent, living memory.

Compare that situation to the one COVID-19, the disease caused by this new coronavirus, presents. No example in recent history is analogous to the present moment. Those that feel similar, such as H1N1 in 2009 and Ebola in 2014, do so only because they are infectious diseases, not because their spread or their impact was similar to this one. COVID-19 is different: It spreads more rapidly, including via asymptomatic hosts. When it strikes hard, it can require ICU treatment, and enough of that demand at once can overwhelm hospitals, as Italy is experiencing.

[Read: The extraordinary decisions facing Italian doctors]

And yet, leaders or citizens have struggled to admit that they know very little about what a reasonable and necessary response might look like in the long run. Health officials recommend staying home if possible, but politicians, such as Representative Devin Nunes of California, have encouraged Americans to dine out in order to support the local economy. Yesterday, the CDC recommended against gatherings of 50 people or more, but some schools and universities resisted changes. Tonight, the University System of Georgia, where I teach, finally announced its intention to move instruction online.

The idea that an extreme reaction, such as closing schools and canceling events, might prove to be an overreaction that would look silly or wasteful later outweighs any other concern. It can also feel imprudent; just staying home isn’t so easy for workers who depend on weekly paychecks, and closing is a hard decision for local companies running on thin margins. But experts are saying that Americans can’t really over-prepare right now. Overreaction is good!

It’s hard to square that directive with the associations we’ve built up around overreactions. Ultimately, overreaction is a matter of knowledge—an epistemological problem. Unlike viruses or even zombies, the concept lives inside your skull rather than out in the world. The sooner we can understand how that knowledge works, and retool our action in relation to its limits, the better we’ll be able to handle the unfolding crisis.

The Y2K bug offers a more complex and therefore more relevant example, and one that, unlike my municipal-snowstorm woes, touched everyone: In the late 1990s, leading up to the year 2000, computing professionals warned that legacy computer systems, programmed to accept dates in a two-year format, were going to wreak havoc when the year suffix turned from 99 to 00. Furthermore, the legacy systems most affected by this problem were also the ones used to run complex and crucial systems, including banks, power plants, and air-traffic control operations, that could incite massive calamity if they went down.

Even so, nobody really knew what would happen if the bugs didn’t get remedied, because testing massive, distributed infrastructures at real-world scale is extremely difficult. In the face of this uncertainty, public and private contractors decided not to ignore the issue, but to do the expensive and onerous work of finding and hiring programmers who still knew the old languages that ran many of the legacy systems, just in case it might prove to be necessary.

Was it worthwhile? We have no idea. Efforts to verify matters have proven elusive: Maybe all the time and money that went into retrofitting old COBOL code on mainframes really did save human civilization as the clocks turned to midnight on January 1, 2000. Or maybe not. Unfortunately, the outcome—Hey! Whatever we did, it worked!—wasn’t celebrated. Instead, the whole affair quickly became an embarrassment, seen by many as a stupid boondoggle that enriched duplicitous consultants.

Of course, had things gone very wrong, the costs of cleanup (not to mention the human costs) would have far exceeded the $100 billion (in America alone!) spent to prevent a calamity. The same is true for COVID-19; already, the U.S. failure to act sooner promises to exact almost unthinkable costs in the near and long term.

It must be nice, on some level, to be a jet-setter or restaurant patron still going about business as usual, as if draped in a magic cloak of protection. But the desire to avoid inconvenience, or to save face, doesn’t mean the people spurning social distancing or mocking school closures know something different than the rest of us about what’s coming. It’s that they don’t know that they don’t know those things. Like the folks running metro Atlanta in 2014, they are making decisions based on something worse even than ignorance, namely the presumption that the knowledge already in hand is sufficient to recommend action.

[Read: The problem with telling sick workers to stay home]

To learn to live with overreactions, you must learn to tolerate waste, to embrace excess. Risking overreaction means knowing, in advance, that a particular action might be extreme and carrying it out anyway. And doing so not under a cloud of nail-biting fear that you might look a fool if it turns out wrong, but in the hopes that having done so will make it turn out right. If it does, you who overreact will earn a response even worse than the shame of looking the fool: Like the heroes of Y2K, you will enjoy no response whatsoever.

The term overreaction once addressed this paradox somewhat, by framing overreaction as an involuntary phenomenon. In earlier usage, it seems to have referred to physiological phenomena, such as the way a muscle or organ might overreact to a physical or chemical stimulus. When the OED first added overreact to the dictionary, in 1919, it offered this example: “The eye under-reacts to acute angles and over-reacts to obtuse angles.” This is one example among the many optical illusions and visual tricks that dupe perception. In this case overreaction isn’t something a human agent should, or even could, feel weird or embarrassed about. It’s just a weird quirk of the mind.

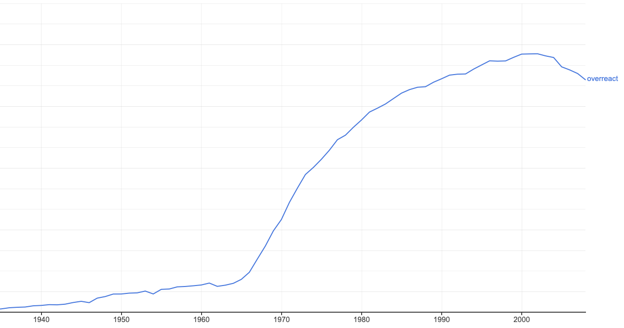

The term remained relatively dormant until the 1960s, when it experienced a huge surge, as illustrated in the Google Ngram graph below.

It’s difficult to pin down exact causes for a concept’s cultural rise, but two domains that rose to prominence during this period offer compelling explanations, even if just in part. The first is the professionalization of psychology and psychiatry, which had already been translating the physiological sense of overreaction into a psychological one. Overreaction had started to transform into a state of mind. Neurotics, for example, might overreact to pain; parents might overreact to a child’s learning disability, swayed by popular literature priming them for the topic.

The second is financialization. With productivity on the rise, American wealth started to accrue through banking and finance, and the wisdom of management gave way to that of equities markets, which had recovered from the Great Depression and World War II. Now businesses, and soon governments, started reacting less to fundamentals in their supply chains, and more to their perceptions of changes in those fundamentals, including on stock charts. Industrialists might, for example, “overreact to demand shifts,” and dairy farmers might “overreact to a price change” in the dairy market.

I’d contend that the surge in use of overreaction since the 1960s also changed the meaning of the term, transforming it from a condition that embraced the paradox of its knowledge into one that resisted it, that felt shame in it, even.

In the case of psychology, for example, overreaction became a problem of individual experience, explainable (and perhaps correctible) through therapeutic or medical treatment—which, of course, the psychiatric profession is happy to provide. And in financial markets, what investors think is happening is just as important, and perhaps even more so, as what can be shown actually to be taking place. Anything people didn’t know about the mind or the market became a defect, subject to possible remedy.

As trends like these amplified, they degraded overreaction’s previous power to account for uncertainty. As a result, overreaction decayed into a sin, a practice of waste and excess instead of one of care and foresight. The Brooklyn Bridge was massively overengineered in order to withstand forces and uses the designers knew they couldn’t know about in 1883, when the structure was built. Almost 100 years later, Citycorp Center, in Midtown Manhattan, was designed in a way that put it at risk of falling over in a bad storm. Certainty became fully calculable, knowledge of the future knowable in the present.

We went wrong when we allowed overreaction to become synonymous with reaction run amok: a crazed, irrational type of action rather than a legitimate way to respond, given a fundamental inability to understand and process stimuli effectively.

Over the past week, actual reactions to the coronavirus started to change. Schools and universities closed. Offices instituted telework. Families cleared out grocery shelves in anticipation of hunkering down for weeks or longer. These efforts come at great personal, emotional, and financial cost. Americans have very real reasons not to want to overreact to coronavirus anxieties. Restaurants in some cities, including New York and Seattle, have been ordered to offer only pick-up and delivery, a shift that will hurt people’s livelihoods and damage the economy. Parents whose kids are suddenly home from school or college now have to attend to their needs somehow. But failing to contain the virus could eradicate those livelihoods and that economy entirely. These high stakes make the paradox so profound.

If we have done too little, too late—a very real possibility—then the impacts of the coronavirus will swell further out of our control, producing catastrophic rather than merely miserable consequences. But if we have done enough, or even well more than enough, then we will have a hard time pinning down which measures ultimately made the difference. Maybe hand-washing will have reduced the virus’s spread. Maybe social distancing will have slowed it enough for medical facilities to handle most serious cases. Maybe shutting down retail and food-service establishments will have reduced the risk of transmission.

What we know now is that we don’t know yet if it will have been enough. That’s an uncomfortable and unintuitive sensation for a human being to have. Instead of fighting that discomfort, we should embrace it. Sometimes we do things even though they don’t make sense, or even because they don’t make sense, because our tiny minds have proven unable to grasp their consequences. In this case, Americans are not conducting this grand social experiment to make ourselves feel comfortable. We are doing it in the hope that later, and maybe even soon, we will look back and find it unreasonable. In the best-case scenario, as with Y2K, we might even look back and mock it for its excess. The point of overreacting, it turns out, is to overreact: to react excessively, but with reason. If you feel at least a little foolish right now, then you’re doing something right.